One of our main priorities is to ensure universal access to, and informed use of effective contraception. Millions of people lack the knowledge and information to determine when or whether they have children, and they are unable to protect themselves against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Articles about Contraception

IPPF lauds news commitments made at London FP Summit

The International Planned Parenthood Federation has praised the Governments, private companies and partner organisations making family planning commitments at today’s London Summit. Speaking at the summit, IPPF Director General Tewodros Melesse said: “IPPF welcomes the wonderful and generous commitments being made today by Governments, civil society and the private sector. As the largest provider of family planning services in the world, IPPF’s members know that access to family planning transforms the lives of women and girls. That is why it is vital that the 214 million women and girls around the world who want contraceptive care but are currently denied it must be given access to it. We know that tens of millions of women and young girls are forced into pregnancy every year because they do not have access to the contraceptive care they want and need. Reproductive rights exist only on paper without supplies. Without generous additional support the world’s poorest women and girls are asked to try to bridge a contraceptive funding gap from their own pockets – something they simply cannot do.” Today’s FP Summit is co-hosted by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Mr Melesse praised the UK Government for its announcement of an increase in funding for family planning of £45m a year for five years, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for its announcement of an additional £375m over four years for global family planning. Mr Melesse said: “These huge additional increases in funding from DFID and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the commitments made by so many other governments, private companies and partner organisations today show we are all united in our determination to reach those woman and girls currently underserved and overlooked. “IPPF has published a new report today which says that more women and girls than the entire population of Germany will find themselves forced into pregnancy just this year because they cannot get the contraceptive care they want and need. The vast majority of them are in developing countries. IPPF’s members work tirelessly to reach the poorest and most marginalised in these societies – we will build on the commitments of the London Summit today to reach even more of them than ever.” Join our campaign: ask for universal access to contraception!

Under-served and Over-looked

Under-served and Over-looked is a flag in the ground. It is a decisive declaration that IPPF stands for equity. IPPF stands for human rights for all. While IPPF has long worked to scale up family planning services, to reduce unmet need and to reach vulnerable populations, with the launch of Under-served and Over-looked we are confirming that reaching the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach groups is IPPF’s top priority. This report is a synthesis of evidence revealed from a literature review, including 68 reports from 34 countries. The results are dire: the poorest women and girls, in the poorest communities of the poorest countries are still not benefitting from the global investment in family planning and the joined up actions of the global family planning movement. Women in the poorest countries who want to avoid pregnancy are one-third as likely to be using a modern method as those living in higher-income developing countries. This is not acceptable. Join IPPF campaign for universal access to contraception

Breaking through barriers to family planning in 21st-century Nepal

The past 15 years have been turbulent for this small, landlocked country. Poverty is widespread and the earthquake of 2015 had a devastating effect. Almost 9,000 people were killed and over 22,000 injured, while the effect on houses and buildings was catastrophic: around 800,000 homes were destroyed or damaged, and 3 million people were displaced. The earthquake hit Nepal’s health sector hard. Clinics were destroyed up and down the country, and for the millions displaced from home and forced into tents, accessing health services – including family planning – became difficult, sometimes impossible. Contraception and family planning: the issues Even before the earthquake, family planning in Nepal was fraught with problems. Around 14 million Nepalis live in mountainous or hilly regions, often in small, remote villages many miles from the nearest town, where health facilities are often scarce, understaffed and poorly supplied with drugs. Where roads exist, they are often potholed, sometimes impassable, making road travel arduous. For the millions of Nepalis living beneath or near the poverty line, travelling on foot is the only option, and, even when they can afford to rent a space in a car, vehicles are scarce. “When I was about to give birth, we called for an ambulance or a vehicle to help but even after five hours of calling, no vehicle arrived,” recalls 32-year-old Muna Shrestha. “The birth was difficult. For five hours I suffered from delivery problems.” Every year, tens of thousands of Nepalis give birth without any medical help at all: just 36% of births are attended by a doctor, nurse or midwife. Maternal mortality is one of the leading causes of death among women. Myths, misconceptions and cultural resistance to contraception A lack of knowledge about family planning and contraception compounds the issue – a problem that becomes even greater among Nepal’s many rural communities and certain ethnic groups. In thousands of households, hostility towards family planning has its roots in deep-rooted customs and beliefs. In Nepal’s largely patriarchal culture, it remains the norm for couples to have four or more children: preference for sons means women are forced to go on having children until boys are born. Contraception remains an alien, uncomfortable idea for millions of Nepalis and is tightly controlled by men: women often need consent from their husbands to use contraception. Misconceptions are also rife. “I’ve heard the coil can cause cancer,” says Muna Shrestha, a farmer from Kavre district. “There are so many side effects to these devices.” In many households, contraception is deemed to fly in the face of ancient cultural traditions. “It’s thought that men who have had vasectomies won’t be able to perform the rituals after their parent’s death,” explains Binu. “Parents think that God won’t accept that, so they don’t allow men to have vasectomies.” Pasang Tamang, an FPAN volunteer in Gatlang, tells of one man who threatened to kill his wife, the doctor and any health worker who provided family planning services to his wife. Spreading knowledge to remote regions Meeting the family planning needs of Nepal’s 28 million people, particularly those living in remote mountain villages, takes careful planning, complex logistics, skilled staff and money. Since 1959, the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), has been providing better access to family planning and maternal health, ensuring its services penetrate even the most remote corners of this rugged mountain country. Reaching communities in far flung parts of this mountainous country is a logistical challenge, but one FPAN sees as crucial to its work. Teams of staff and volunteers spend days travelling by vehicle or, if necessary, on foot to make sure they reach people. “Accessibility is a big challenge, especially in rainy season when the road gets blocked and our staff have to walk carrying all the devices,” says Devendra Amgaim, FPAN’s project coordinator in Rasuwa, northern Nepal. “I go to remote places, where people and don’t know about family planning,” says Binu Koraila, an FPAN staffer in Rasuwa. Her role is spread knowledge about family planning and contraception among rural communities and to train the government workers who staff the health posts, many of which are many hours’ walk from the hamlets and villages that perch on the Langtang mountains. Cultural beliefs High up in the mountains of northern Nepal, close to the border with Tibet, lies the village of Gatlang. This cluster of timber-framed houses and Buddhist stupas is home to some of Nepal’s 1.5 million Tamang people, an ethnic group with cultural traditions stretching back centuries. Life here is strictly patriarchal. Marriage often takes place young – from around 14 years old – and girls are given little choice about when or whom they will marry. “My parents forced me to get married,” says 20-year-old Jomini. Jomini married at the age of sixteen, to a man eight years her senior. “It’s not easy being married, it’s difficult,” she says. “When I got married, I didn’t know anything about what happens after marriage, about the physical side … and after the birth of my first child I had many difficulties.” According to Nepali law, marriage under the age of 20 is illegal. But over 40% of 20 to 24 year olds are married before they turn 18. The effect on girls’ lives can be devastating: physical problems from teenage pregnancy, psychological trauma, thwarted education and employment opportunities are widespread, particularly in remote regions. Access to contraception means nothing unless people understand why it is important and make the decision – armed with the correct information – to use it freely themselves. Busting the myths that can shape people’s ideas about family planning is complex but vital. FPAN does it by spending time and resources on teams who go in and talk to women and families in ways that are tailored to their needs. “Rasuwa district has a very low literacy rate, so FPAN … gives people the right information about family planning using visual aids, images and charts,” Devendra Amgaim explains. “Reproductive health female volunteers also translate information into local languages. All this helps make information simpler, more effective and easily understandable.” The organisation strives to make sure it is sensitive to the structures that shape life in Rasuwa. This is also pragmatic: once you have won the trust and confidence of community leaders, it is much easier to talk to the rest of their community. “FPAN seeks out the people who have influence in the communities – the religious leaders, the teachers, the female voluntary workers,” Devendra says. “We give them orientation and knowledge regarding those misconceptions. They then create awareness.” Stories Read more stories from Nepal

Bringing contraceptive choice to mountain communities

Meeting the family planning needs of Nepal’s 28 million people, particularly those living in remote mountain villages, takes careful planning, complex logistics, skilled staff and money. Since 1959, the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), has been providing better access to contraception and maternal health, ensuring its services penetrate even the most remote corners of this rugged mountain country. Reaching communities in far flung parts of this mountainous country is a logistical challenge, but one FPAN sees as crucial to its work. Teams of staff and volunteers spend days travelling by vehicle or, if necessary, on foot to make sure they reach people. Stories Read more stories from Nepal

How cultural traditions affect women’s health

High up in the mountains of central northern Nepal, not far from the Tibetan border, lies the district of Rasuwa. The people here are mainly ethnic Tamang and Sherpa, two indigenous groups with cultural traditions stretching back centuries. But these rich cultural traditions can come hand-in-hand with severe social problems, compounded by entrenched poverty and very low literacy rates. Binu Koraila is a health facility mentor for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN) in Rasuwa. "Stigma, myths and cultural practices can have a damaging effect on sexual health, family planning and women’s rights", she says. Misconceptions about contraception are widespread. “People think the intrauterine coil will go into the brain or will fall out. They think the contraceptive implant will penetrate into the muscles.” Funeral rites present another problem. “Men who want a vasectomy need permission from their parents,” she explains. “But it’s thought that men who have had vasectomies won’t be able to perform the rituals after their parent’s death: parents think that God won’t accept that, so they don’t allow men to have vasectomies.” The culture here is strongly patriarchal. Among the Tamang, marriage involves boys or men picking out young girls from their communities.Early and forced marriage is widespread among the Tamang. If chosen, the girls have no choice but to get married. “If a boy likes a girl, they can just snatch them and take them to their house,” Binu says. Some girls are as young as 13 years old. “The girls don’t know enough about family planning, so there is a lot of teenage pregnancy.” Early marriage and teenage pregnancy can create all kinds of physical, emotional, social and economic problems for girls and their families. For many, their bodies are not well developed enough for childbirth, and maternal mortality remains a major problem in Nepal, at 258 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to UNFPA data. Their large families also suffer because there is not enough food and money to go around. “Women are the worst affected,” Binu says. Parents and husbands keep strict control of women’s access to contraception. “If they want to use contraception, women tend to need consent from their parents or husbands. “I have seen cases where if a woman gets contraceptive implant services, they get beaten by their father-in-law and husband. One woman asked to have her implant removed because she had been beaten by her husband.” Binu’s role is to deliver sexual health and family planning advice and services to villages across Rasuwa district: “I go to remote places, where people are marginalised and don’t know about family planning.” She also trains government health workers on family planning, and mentors them after they return from training in Kathmandu to Rasuwa. As well as delivering health services, the FPAN team have been working hard to change perceptions. “Recently we had a health camp at Gatland,” she explains. "After two hours of counselling one client requested an IUD. After months there was a rumour in Gatlang that her coil had fallen out. The FPAN volunteer went to the woman’s house and asked if this was true. She said, ‘No, I’m really comfortable with that service.’ After that, the client went door to door and told others how happy she was with it and that they should take it at the next family planning camp. “After four or five months, we went back to the Gatlang camp and at that time another eight women took the IUD.” These numbers might seem small but they are far less so when viewed against the wall of stigma and myth that can obstruct contraception use here, as in so many rural areas of Nepal. The involvement of committed, passionate health mentors and volunteers is vital to show people how important it is to take sexual health and family planning seriously: the benefits are felt not just by women and their families, but by entire communities. Stories Read more stories from Nepal

Battling stigma against sexual and reproductive health and information

“People used to shout at me when I was distributing condoms. ‘You’re not a good girl, you’re not of good character’ they’d say. They called me many bad things.” “But later on, after getting married, whenever I visited those families they came and said: ‘you did a really good job. We realise that now and feel sorry for what we said before.” Rita Chawal is recalling her time as a volunteer for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), Nepal’s largest family planning organisation. Her experiences point to the crucial importance of family planning education and support in Nepal, a country still affected by severe maternal and infant mortality rates and poor access to contraception. Poor government services, remote communities, a failing transport network and strict patriarchal structures can make access to family planning and health services a challenge for many people across the country. Services like FPAN’s are vital to reach as many people as possible. Rita is now 32 years old and herself a client of FPAN. She lives with her husband and six-year-old son in Bhaktapur, an ancient temple city, 15 kilometres from the centre of Kathmandu. Before getting married, she spent 10 years working as a family planning youth volunteer for FPAN, running classes on sexual health, safe abortion and contraception. Her time at the organisation set her in good stead for married life: after marrying she approached FPAN right away to get family planning support, antenatal classes, and, later on, contraception. “I had all this knowledge, so I decided to come and take the services,” she says. “I found that the services here were very good.” But Rita is far from the norm. She shudders when she recalls the abuse she received from neighbours and her community when she worked distributing contraception. Stigma still surrounds contraception in many places: for an unmarried young woman like Rita to be distributing condoms was seen as immoral by many, particularly older, people, even in an urban setting like Bhaktapur. Stigma can be even more extreme in rural areas. Across Nepal, rumours about the side effects of different contraceptive devices are also a problem. Attitudes are slowly changing. Rita says people now come to her whenever they have a family planning problem. “I have become a role model for the community,” she says. She herself is now using the contraceptive implant, a decision she arrived at after discussing different options with FPAN volunteers. She has tried different methods. After her son’s birth, she began using the contraceptive injection. “After the injection, I shifted to oral pills for six months, but that didn’t suit me,” she says. “It gave me a headache and made me feel dizzy. So I had a consultation with FPAN and they advised me to use the implant. I use it now and feel really good and safe. It’s been five years now.” This kind of advice and support can transform the lives of entire families in Nepal. Reductions in maternal and infant mortality, sexual health, female empowerment and dignity, and access to safe abortion are just a few of the life-changing benefits that organisations like FPAN can bring. Stories Read more stories from Nepal

Waiting for an ambulance that never arrives: childbirth without medical help in rural Nepal

“When I was about to give birth, we called for an ambulance or a vehicle to help but even after five hours of calling, no vehicle arrived,” recalls 32-year-old Mona Shrestha. “The birth was difficult. For five hours I had to suffer from delivery complications.” Mona’s story is a familiar one for women in rural Nepal. Like thousands of women across the country, she lives in a small, remote village, at the end of a winding, potholed road. There are no permanent medical facilities or staff based in the village of Bakultar: medical camps occasionally arrive to dispense services, but they are few and far between. Life here is tough. The main livelihood is farming: both men and women toil in the fields during the day, and in the mornings and evenings, women take care of their children and carry out household chores. The nearest birthing centre is an hour’s drive away. Few families can afford to rent a seat in a car, and so are forced to do the journey on foot. For pregnant women walking in the searing heat, this journey can be arduous, even life-threatening. “Fifteen years ago, there was a woman who helped women give birth here, but she’s no longer here,” Mona says. “It’s difficult for women.” Giving birth without medical help can cause severe problems for women and babies, and even death. Infant mortality remains a major problem in Nepal, and maternal mortality is one of the leading causes of death among women. Only 36% of births are attended by a doctor, nurse or midwife. A traumatic birth can cause long-term physical, psychological, social and economic problems from which women might never recover. Access to contraception and other family planning services, too, involves walking miles to the nearest health clinic. Mona says she used to use the contraceptive injection, but now uses an intrauterine device. Like many villages in Nepal, Bakultar is awash with myths and gossip about the side-effects of contraception. “There are so many side effects to these devices – I’ve heard the coil can cause cancer,” Mona says. “This is why we want to have permanent family planning like sterilisation, for both men and women.” These complaints heard frequently in villages like Bakultar. As well as access to facilities and contraception, people here desperately need access to education on contraception and sexual health and reproductive rights. Misinformation as well as a lack of information are both major problems. “It would be really helpful to have family planning services nearby,” says Mona. Stories Read more stories from Nepal Ask for universal access to contraception!

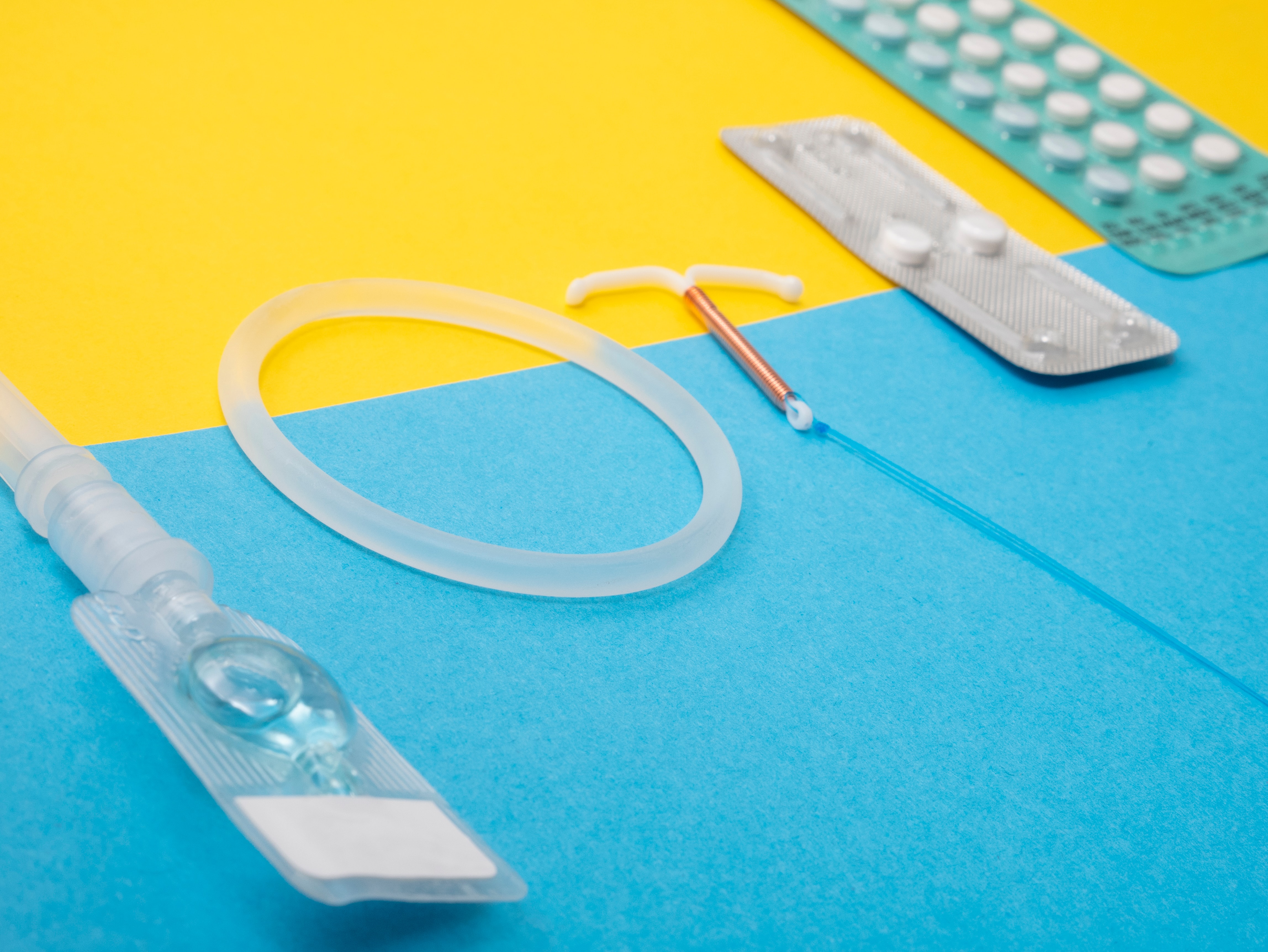

Myth-busting facts about IUDs

Intra-uterine devices are safe, reliable and can be used by almost everyone. Want to know more about them? We've got you covered! Learn about other methods of contraception

Sayana Press: empowering women with the ability to administer their contraceptive of choice

Every year, hundreds of millions of women in Sub-Sahara Africa travel to their local health clinics to receive regular contraceptive injections. Injectables are popular because they are safe, discrete, highly effective at preventing unintended pregnancy, and last for several months. However, for many women, travelling to a clinic to receive a contraceptive injection is not feasible. The costs of travel are too great; the distance too far; and the time spent away from family or work too great a challenge to overcome. Sayana Press has the potential to address these problems, and in doing so, bring injectable contraception within reach of women millions of poor women who might not otherwise be able to prevent unintended pregnancies. Unlike traditional injectables, Sayana Press can be administered by any (non-medical) person who has received minimal training - including community health workers, pharmacists, and crucially, by women themselves. This is because, unlike traditional traditional injectables, Sayana Press has a user-friendly design that makes it safe and easy to use. It is injected just below the skin (subcutaneously) rather than deep into the muscle, and comes in an ‘all in one’ injection system - rather than in a vial with a separate syringe like traditional injectables. IPPF along with other global service delivery partners, such as Marie Stopes International (MSI), Population Services International (PSI), and PATH are playing an important role in introducing Sayana Press to under-served communities. By using their systems, technical capability, and community-level presence, these partners are galvanising on Sayana Press’s potential role help reduce unmet contraceptive need and reach new users. Specifically, with support from USAID through SIFPO-2, IPPF's Ugandan Member Association, Reproductive Health Uganda, is leading the introduction of Sayana Press, as part of a comprehensive mix of methods, in four rural districts within Uganda. Public health providers and community workers are trained to counsel women in a full range of family planning methods, and their side-effects, so that they can make a full, informed and voluntary choice. As regulatory approval for injectables is being granted in more and more countries, there is an opportunity to apply lessons from early-adopter regions where Sayana Press is already being provided. Recently, with support from USAID, IPPF convened a technical workshop with PSI and MSI to collaboratively prioritise the expansion of quality access to Sayana Press, so that more marginalized women with the greatest unmet need for family planning can also benefit from this option. Attendees came from Kenya, Uganda, Burkina Faso, Zambia, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, Madagascar and the Democratic Republic of Congo. They developed plans and strategies for to increase access to Sayana Press and other methods in their countries. Together, the efforts of these partners will reduce the unmet need of the 225 million under-served women and girls around the world, who want to use contraception but can’t get it. Sayana Press is part of this puzzle which will improve the lives of these women and girls.

Humanitarian crises are not temporary, nor are sexual and reproductive health needs

Women and girls are disproportionately affected in humanitarian crises and face multiple sexual and reproductive health challenges in these contexts. IPPF has been providing much needed support to vulnerable communities through our global federation of member associations, who provide contextualised, timely and tailored interventions drawing on local partners' knowledge and expertise. However, recent shifts in the global political landscape are concerning and threaten to undermine IPPF's mission and impact on the ground. We live in a time when crises, whether brought on by human causes or natural disaster, have displaced more people than at any point since the Second World War. The needs of those driven from their homes are not transitory. Refugees now find themselves facing impermanent conditions for an average of 20 years. They must resort to living in temporary shelters or makeshift accommodation, and their refugee status often leaves them ineligible to access public healthcare and education. The UN reports there are more than 125 million people worldwide in need of humanitarian assistance. Of those, a quarter are women and girls between the ages of 15 and 49. And one in five of these women and girls is likely to be pregnant. A woman who has been forced to flee is particularly vulnerable. More than 60% of maternal deaths take place in humanitarian and fragile contexts, according to the UN Population Fund (UNFPA). At least half of these women’s lives could easily be saved. And yet women and girls affected by humanitarian crises face other risks too. A breakdown in civil order following disasters consistently increases the occurrence of sexual violence, exposure to sexually transmitted infections including HIV, and unintended pregnancies. After the 2015 cyclone in the Pacific Island nation of Vanuatu, a counselling centre recorded a 300% spike in gender-based violence referrals. Likewise, a study with Syrian refugee women displaced by conflict found that more than 50% experienced reproductive tract infections, almost a third had experienced gender-based violence, and the majority had not sought medical care. IPPF is at the forefront of delivering life-saving services. Our sexual and reproductive health program in crisis and post-crisis situations (SPRINT), established in 2007 and supported by the Australian Government, has ensured access to essential sexual and reproductive health services for women, men and children in times of crisis. Under the banner of our new IPPF Humanitarian division, the SPRINT initiative is now part of a global movement that seeks to provide all those affected by crises worldwide with dignity, protection and care. As a federation of 142 locally-owned but globally connected member associations, IPPF has a unique model for providing these vital humanitarian services. Our focus on valuing local solutions means our responses are rapid and sustainable. We see it as vital to be on the ground before, during, and after crises. Member associations work to mitigate against sexual and reproductive health (SRH) issues ahead of a crisis to reduce negative impacts, and remain afterward to assist communities to recover and rebuild their lives. When Cyclone Winston struck Fiji in February last year, IPPF’s local member association, the Reproductive and Family Health Association of Fiji (RFHAF), was already preparing to mobilise teams of volunteers and health staff. Initially, sexual and reproductive health was not prioritised at a national level, thus the first challenge was to convince the Government of Fiji and lead agencies of the critical importance of including sexual and reproductive health issues in the response. With support from IPPF and SPRINT personnel, RFHAF successfully advocated with the government to include reproductive health concerns into the post-cyclone needs assessment, and supported the Government in carrying this assessment out. Coordination and collaboration was critical as the damage was across an extensive area on several islands. Working in partnership with the Ministry of Health (MoH), UNFPA, Red Cross Society and local non-government agencies, RFHAF provided SRH care to remote areas identified as being worst hit by the cyclone. Colleagues from SPRINT and RFHAF split into three teams, moving into the field simultaneously to conduct 37 mobile medical missions to reach women and girls, with vulnerable pregnant women and new mothers prioritised. Comprehensive follow up beyond the initial response post-cyclone was a particular challenge for an organisation of just 11 staff. To address this, RFHAF leveraged their existing partnership with the MoH to facilitate training and handover of SRH service provision to district nurses and sub-divisional health centres, once these facilities were again operational. The response in Fiji utilised the Minimum Initial Service Package for Reproductive Health, which IPPF helped to pioneer. Commonly referred to as ‘the MISP’, the package is a series of priority life-saving interventions that IPPF seek to implement as soon as possible following a crisis.

Pagination

- Previous page

- Page 10

- Next page